A Pacific Ocean crossing is not in the cards for us on AquaVida. In some ways I am ok with that as sailing the Pacific is far different from the Caribbean. A forty-day journey from the Panama Canal to the Marquesas, then a series of long open water runs as you go across the Pacific are a completely different animal than the day to day sailing of the Caribbean. No matter how calm people tell you the trip will be, forty-days is a long time to go without seeing another boat. Danielle and Kaylee could not get their heads around this trip and with the potential for bouts of seasickness I could not blame them.

I was however given my chance to do a little blue water sailing with our friend Dan on Vagabond. That’s Dan Daniels sailing a Vagabond 47 named Vagabond 47. We met at Blacks Island Bahamas as he was triumphantly walking back to the anchorage boasting of the fact that he had found and bought the last dozen eggs on the island. We crisscrossed paths, meeting again in Christmas Cove, Virgin Islands where he greeted us with a fresh baked pizza from the pizza boat in the anchorage. We later climbed Mt. Nevis together and picked him up in St Kitts as he rode shotgun on the ill-fated trip to get S/V Pepper to a boatyard before she sank due to a giant gash opening in her hull. Pepper never made it back in the water and her crew Trent and Monica are back home in the States getting on with life.

So are the times and friendships developed as you take the time to cruise any part of the world. We continued to follow Dan and Vagabond as he steamed ahead of us through Colombia, the Panama Canal and across the Pacific. Dan is a “single handed” sailboat captain which in this case means he lives on his boat by himself and relies on friends, family, hitchhickers or anyone else (experienced or not) to help him as he moves from place to place. And that is how I got my invitation; he was in Tahiti and realized he only had crew through Fiji and knew he had a thousand-mile trek to New Zealand without help. We got the call, or more correctly the text that he needed crew.

New Zealand is on everyone’s bucket list and the idea of getting a chance to sail there was really tempting. We had left AquaVida in Colombia in August for hurricane season and could not return until January. We were wearing out our respective welcomes at parents' and children’s homes across the southeast, so we had a couple of months to kill and what better way than trekking through New Zealand, especially given the excuse to help deliver a yacht from Fiji to Opua. It really was a no-brainer.

Of course, we took Dan up on his offer and began planning, or as much planning as Danielle and I do, which isn’t much. At first, we were all going to do the sail with Dan but as we began to research the trip Danielle and Kaylee quickly opted for the flying to Auckland route to meet us when we arrived in the Bay Islands in the north.

Dan was able to get another friend, Peter, a TV producer from Toronto and a seasoned traveler to sign on as the third crew. In simple planning terms, a 1000-mile voyage is about 10-days at sea and three people gave us a nice watch rotation of 4 hours on and 8 off. You can do the math. Two people over 10 days would be a rough trip. Danielle and I had done three-day trips and we were worn out by the time we made port.

I arrived in Fiji on October 12th. Upon arrival I got a text from Danielle that Vagabond was still in the out islands and a few days out from the Vuda Marina just north of Nadi, the main international airport of Fiji. Such is the way of all sailing trips, you get to pick the time or the place but not both, so I knew Dan would be in Nadi but only knew about when he might arrive. At the airport I got a cab and asked him to take me to a clean but inexpensive hotel where I could wait for Vagabond to arrive.

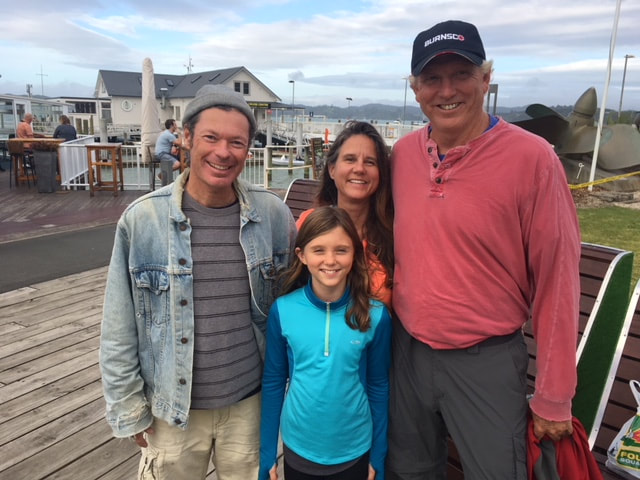

I did a little bit of my version of touristy stuff; took the public bus into the backcountry looking for some places to hike, visited an orchid garden, ate some great Indian food and two days later finally decided to change venues and move closer to the marina. Dan would either show up or I would find lodging around there. Late that afternoon I ran into another friend, Thom, from S/V Fathom, another single hander from the UK. Thom is a true single-handed sailor, sailing his 28-foot boat from England on his circumnavigation. We met Tom in Santa Marta, Colombia, on our 5-day trek to La Ciudad Perdida only to later find out he was living in the same marina as us. Fathom is another boat we have since been following through his blog, so when we met up it was like we had not missed a beat. A few beers together and he was able to give me the basic low-down on the marina and the various characters that were here. And the timing was perfect as a few hours later Dan came roaring into the marina in his dinghy with Cheryl, his new girlfriend and Peter, my crewmate.

I was however given my chance to do a little blue water sailing with our friend Dan on Vagabond. That’s Dan Daniels sailing a Vagabond 47 named Vagabond 47. We met at Blacks Island Bahamas as he was triumphantly walking back to the anchorage boasting of the fact that he had found and bought the last dozen eggs on the island. We crisscrossed paths, meeting again in Christmas Cove, Virgin Islands where he greeted us with a fresh baked pizza from the pizza boat in the anchorage. We later climbed Mt. Nevis together and picked him up in St Kitts as he rode shotgun on the ill-fated trip to get S/V Pepper to a boatyard before she sank due to a giant gash opening in her hull. Pepper never made it back in the water and her crew Trent and Monica are back home in the States getting on with life.

So are the times and friendships developed as you take the time to cruise any part of the world. We continued to follow Dan and Vagabond as he steamed ahead of us through Colombia, the Panama Canal and across the Pacific. Dan is a “single handed” sailboat captain which in this case means he lives on his boat by himself and relies on friends, family, hitchhickers or anyone else (experienced or not) to help him as he moves from place to place. And that is how I got my invitation; he was in Tahiti and realized he only had crew through Fiji and knew he had a thousand-mile trek to New Zealand without help. We got the call, or more correctly the text that he needed crew.

New Zealand is on everyone’s bucket list and the idea of getting a chance to sail there was really tempting. We had left AquaVida in Colombia in August for hurricane season and could not return until January. We were wearing out our respective welcomes at parents' and children’s homes across the southeast, so we had a couple of months to kill and what better way than trekking through New Zealand, especially given the excuse to help deliver a yacht from Fiji to Opua. It really was a no-brainer.

Of course, we took Dan up on his offer and began planning, or as much planning as Danielle and I do, which isn’t much. At first, we were all going to do the sail with Dan but as we began to research the trip Danielle and Kaylee quickly opted for the flying to Auckland route to meet us when we arrived in the Bay Islands in the north.

Dan was able to get another friend, Peter, a TV producer from Toronto and a seasoned traveler to sign on as the third crew. In simple planning terms, a 1000-mile voyage is about 10-days at sea and three people gave us a nice watch rotation of 4 hours on and 8 off. You can do the math. Two people over 10 days would be a rough trip. Danielle and I had done three-day trips and we were worn out by the time we made port.

I arrived in Fiji on October 12th. Upon arrival I got a text from Danielle that Vagabond was still in the out islands and a few days out from the Vuda Marina just north of Nadi, the main international airport of Fiji. Such is the way of all sailing trips, you get to pick the time or the place but not both, so I knew Dan would be in Nadi but only knew about when he might arrive. At the airport I got a cab and asked him to take me to a clean but inexpensive hotel where I could wait for Vagabond to arrive.

I did a little bit of my version of touristy stuff; took the public bus into the backcountry looking for some places to hike, visited an orchid garden, ate some great Indian food and two days later finally decided to change venues and move closer to the marina. Dan would either show up or I would find lodging around there. Late that afternoon I ran into another friend, Thom, from S/V Fathom, another single hander from the UK. Thom is a true single-handed sailor, sailing his 28-foot boat from England on his circumnavigation. We met Tom in Santa Marta, Colombia, on our 5-day trek to La Ciudad Perdida only to later find out he was living in the same marina as us. Fathom is another boat we have since been following through his blog, so when we met up it was like we had not missed a beat. A few beers together and he was able to give me the basic low-down on the marina and the various characters that were here. And the timing was perfect as a few hours later Dan came roaring into the marina in his dinghy with Cheryl, his new girlfriend and Peter, my crewmate.

In typical Dan fashion, he had anchored outside the marina with the intent on checking out the environs. He was originally going to just stay outside which is typical of sailors on a budget, free anchorage versus paying for a slip. However, the wind was blowing, Vagabond was bashing, and Peter and Cheryl both squashed the idea for the calm waters of the basin. A really good choice.

It was great to see Dan and meet Peter. I was the last on-board so gave Peter his due as he had been sailing the out islands for the last week with Cheryl and Dan. I had been in Fiji long enough and Peter was also keen to keep going so we began making the boat ready for the crossing. This mostly entailed provisioning and cooking, so we could easily prepare meals under rolling conditions. Peter was a very good cook, Dan, not so much so we collaborated on a nice stew and chili, getting one of our neighboring boat friends to allow us to use their food sealer to make meal size portions. We stored up on fresh vegetables and some smoked chickens.

In the meantime, we canvased the marina and found those looking to make the trek to New Zealand. This is an interesting time of year here and an equally formidable stretch of water. The boats in the marina were a combination of those like Dan, working their way westward, either to end their voyage in New Zealand or Australia and sell their boat, or to lay up for cyclone season, just as we had done in Colombia and to continue their quest for a circumnavigation in May. The other group was New Zealanders that sail into this area for the season, to return home before cyclones hit. I was to learn that everyone here plays a kind of chess game with the weather. You can pick a relatively good window early but know you will get bashed sometime in the 10-day or wait longer to possibly get a calmer, smoother ride but have the potential to face a cyclone and get caught in Fiji. November 1st was the beginning of cyclone season, like the June 1 deadline we have in the Caribbean. Peter and I were pushing earlier than later (weather permitting or course).

A group of six boats had made their decision to leave on Wednesday and we were busy getting Vagabond ready. I was not really sure why, but Dan seemed hesitant to leave on the appointed day and continued to add various chores to his growing list. Peter and I continued to knock these tasks out while Dan procrastinated. We finally put our foot down, we were leaving today, the weather looked good, we were the last of the group in the marina, we needed to go!

As the sun began to set we had a nice 15 knot wind and we were able to get all the sails on Vagabond up and were doing a nice 6+ knots, fast for Vagabond. Thom on Fathom had left earlier for Brisbane, following the same track as us for the first 30 miles before heading west through another pass in the reef. Another boat, a couple of French brothers, who had sailed the Northwest Passage last year (one of only a handful of boats to do so) zoomed by us in their DuFour 34 trying to catch Thom who had a 3-hour head start. They would eventually beat Thom as they always sailed full bore on a larger boat through all sea conditions.

It was the perfect beginning to the sail until a loud bang sounded on board. We did not feel like we hit anything and we all began investigating where the sound had come from. Unfortunately, it was the forward stay on the port side for the main mast, the chain plate holding the cable to the hull of the boat had completely sheared through and was swinging across the deck. We quickly turned downwind and dropped all the sails to not damage the mast. We put a line on the cable to secure it and sadly turned back for Vuda Marina, a four-hour motor now in the dark.

Our work was not finished for the evening as the wind picked up and we had to find the very small and rock protected channel of Vuda Marina. Lights can be confusing in the dark. There is little depth perception and it is often difficult to distinguish which light is outboard. Dan was at the helm, crabbing into the wind and I was at the bow giving him hand signals to direct him towards the seaward buoy and we quickly slid inside the suddenly very small basin, trying to slow down to maneuver into the tight area. We moored to the buoy in the center of the marina, stressed out but secure for the night. We broke open a few beers.

In the meantime, we canvased the marina and found those looking to make the trek to New Zealand. This is an interesting time of year here and an equally formidable stretch of water. The boats in the marina were a combination of those like Dan, working their way westward, either to end their voyage in New Zealand or Australia and sell their boat, or to lay up for cyclone season, just as we had done in Colombia and to continue their quest for a circumnavigation in May. The other group was New Zealanders that sail into this area for the season, to return home before cyclones hit. I was to learn that everyone here plays a kind of chess game with the weather. You can pick a relatively good window early but know you will get bashed sometime in the 10-day or wait longer to possibly get a calmer, smoother ride but have the potential to face a cyclone and get caught in Fiji. November 1st was the beginning of cyclone season, like the June 1 deadline we have in the Caribbean. Peter and I were pushing earlier than later (weather permitting or course).

A group of six boats had made their decision to leave on Wednesday and we were busy getting Vagabond ready. I was not really sure why, but Dan seemed hesitant to leave on the appointed day and continued to add various chores to his growing list. Peter and I continued to knock these tasks out while Dan procrastinated. We finally put our foot down, we were leaving today, the weather looked good, we were the last of the group in the marina, we needed to go!

As the sun began to set we had a nice 15 knot wind and we were able to get all the sails on Vagabond up and were doing a nice 6+ knots, fast for Vagabond. Thom on Fathom had left earlier for Brisbane, following the same track as us for the first 30 miles before heading west through another pass in the reef. Another boat, a couple of French brothers, who had sailed the Northwest Passage last year (one of only a handful of boats to do so) zoomed by us in their DuFour 34 trying to catch Thom who had a 3-hour head start. They would eventually beat Thom as they always sailed full bore on a larger boat through all sea conditions.

It was the perfect beginning to the sail until a loud bang sounded on board. We did not feel like we hit anything and we all began investigating where the sound had come from. Unfortunately, it was the forward stay on the port side for the main mast, the chain plate holding the cable to the hull of the boat had completely sheared through and was swinging across the deck. We quickly turned downwind and dropped all the sails to not damage the mast. We put a line on the cable to secure it and sadly turned back for Vuda Marina, a four-hour motor now in the dark.

Our work was not finished for the evening as the wind picked up and we had to find the very small and rock protected channel of Vuda Marina. Lights can be confusing in the dark. There is little depth perception and it is often difficult to distinguish which light is outboard. Dan was at the helm, crabbing into the wind and I was at the bow giving him hand signals to direct him towards the seaward buoy and we quickly slid inside the suddenly very small basin, trying to slow down to maneuver into the tight area. We moored to the buoy in the center of the marina, stressed out but secure for the night. We broke open a few beers.

The morning came around and we were no better off in the light of day than we were when we tied up last night. Earlier, when leaving Panama and four days into the Pacific Dan lost the forward lower chain plate on the starboard side. He had that one replaced. Now a second one had broken completely through so knowing what we now knew about the potential for hard weather, we agreed they all needed to be replaced. Peter and I set about removing all the chain plates as Dan got a cab and went in to Lakotoa, the port town 10 miles north to find someone who had stainless steel stock.

It took us most of the day and we now had one set of the chain plates from each side off so that they could be used a template. Dan unfortunately could not find any stainless stock on the island and shipping it here would take over a week. Dan was forced to spend the money to make the chain plates out of regular steel, then do them again once we were in New Zealand in stainless. Not a good deal for Dan but the fear of losing his crew and potentially getting stuck in Fiji was enough to motivate him and to his credit he took the templates in and had new ones fabricated by the next day. We spent the next day installing the new chain plates that had already begun getting the light patina of rust, tuned the rigging and began looking at weather. It was a big pill for Dan to swallow but it was done. Peter and I were still here, and we could begin looking at leaving.

It took us most of the day and we now had one set of the chain plates from each side off so that they could be used a template. Dan unfortunately could not find any stainless stock on the island and shipping it here would take over a week. Dan was forced to spend the money to make the chain plates out of regular steel, then do them again once we were in New Zealand in stainless. Not a good deal for Dan but the fear of losing his crew and potentially getting stuck in Fiji was enough to motivate him and to his credit he took the templates in and had new ones fabricated by the next day. We spent the next day installing the new chain plates that had already begun getting the light patina of rust, tuned the rigging and began looking at weather. It was a big pill for Dan to swallow but it was done. Peter and I were still here, and we could begin looking at leaving.

While we waited for the chainplates to be made Peter and I took the car Dan rented for a trip around the island. No real idea where we were going or what we were going to do. Our only notion was that we had heard that the source for Fiji water was somewhere on our side of the island. Fiji water is the high priced bottled water purified by volcanic rock that you find all over the US and Canada. We asked a number of people and received the same response you get on any island, just down that way awhile, then turn. We came upon a random Fiji sign with a small arrow down a little road and turned. A couple of miles down we came upon the modern looking plat. The plant was clean and professionally run. The security guard called one of the site superintendents who happily gave us a tour. It was very high tech and everyone there had nothing but good things to say about the plant. The internet claims only 47% of Fijians have access to potable water and that a full 15% of its water is exported. The owners paying only pennies per bottle of water extracted.

In the meantime, we had learned that weather had turned badly for our friends out ahead of us. They had been bashed with 30+ knot winds on the nose for over three days. Motoring into waves at that windspeed is not fun. We were in the same weather window as when we had left four days ago but it was improving, and our next try looked to be in much better wind conditions. But as everyone knows you can only believe the weatherman so much. Maybe our unfortunate delay would result in better conditions than what we would have received had we continued.

It was time to go again, the weather was fair, the outlook good and staying any longer would have resulted in Peter either taking over the ship or him leaving. I’m glad he stayed, he would later wish he had left when he had the chance.

Five hours downwind and leaving the safe confines of the inland reef-protected waters we entered the open ocean and relatively clean sailing. This was short lived as nightfall fell around us. As always happens, if something is going to happen it will happen in the darkness hours. We had chosen, or more accurately assigned our watches. Peter got the mid-night to four am, noon to four pm watch. To me that is the worst, starting and finishing in the darkness. I chose the 4 to 8 am/pm watch. I love watching the sun come up and I psychologically react to the light. Dan took the 8 to noon and 8 to mid-night. As night arrived, so did the wind and waves, going from below 20 to +30 knots and seas reaching more than 10’, and of course it started to rain.

The boat began to rack around, and we heard the crash and breaking of glass. I was just off watch, Dan and Peter were hanging on in the cockpit and I knew the broken glass would end up getting someone cut so, feeling good, I went down and spent the next 30 minutes on my hands and knees picking up the remnants of the French press in the rolling galley. I was a little worried that the conditions would put me over the edge. I am not normally affected by sea sickness, but this was a different story. I was able to get some air, eat a couple of peanut butter crackers then climb down into the bunk for some sleep.

While Peter got the worst watch I ended up with the forward berth. At anchor the forward berth gets the best breeze. In calm conditions it is spacious and comfortable, in rough conditions it moves far more than anywhere else on-board. The bow rises into the wave and crashes down the other side slamming into the back of the wave. On Vagabond it sounded like someone was smashing the front hull with a huge base drum mallet. You could feel the bow shaking. I rolled around in the waves, trying to steady myself and get a flat and comfortable as possible, all the while realizing that my stomach was beginning to feel a little queasy. Usually I can mentally put myself in a frame of mind to see a bout of sea sickness through but as I started burping peanut butter I thought it best to head up to get some air. I didn’t make it and luckily the head was right there as everything came up, for a long time! Who knows if it was just the waves, the cleaning of the broken glass, the peanut butter. All I could think about was Kaylee would feel so vindicated that I had gotten seasick. But I felt so much better now.

I came on watch at 4 am and Peter and Dan promptly crashed. This was Peter’s first hard night of watch and Dan stayed up with him. Eight hours of rain, wind, waves and bashing. As daylight arrived, the seas calmed a little and the rain stopped. We put up more sail, shut down the iron genie and took 25’s off the beam in a much more comfortable 6 to 10’ sea state. Vagabond is a heavy, full keeled boat and does better under sail. Wind off the beam gave her the best possible speed profile. We were able to maintain minimums of 5 knots and often went hours at over 6 and hit 8’s from time to time.

Having the first night to be so rough put us all a little on edge. I was beginning to wonder why I even liked sailing. I was wet (did I tell you that Vagabond leaked from the waves and rain and my bedding was perpetually wet), I was cold (we spent our night-time watches in full foul weather gear with sweat pants and jackets underneath), and it was too rough to really cook anything (if I could have eaten it anyway). The weather did however improve over the day and we all began to fall into our routine, we had nine days to go and getting to New Zealand was the only way we where going to get off this boat.

Because we had done our repairs so fast and the weather window was holding, we were able to call by single sideband radio into the rest of the group that was five days ahead. They had gone through much worse than we had last night, and for much longer. We could only imagine how they fared hanging on in those high winds and waves for three days. The weather had calmed way down for them and they were doing much better. In a few more days all their morale had improved to the point that they seemed to have forgotten the first part of the trip. I'm sure looking at only a couple of days left had a huge impact on their spirits. You could hear it in the radio calls. We still had 8-days.

By the end of the second day I was pretty much back to my normal self, feeling that sailing wasn’t so bad after all. We were able to sip soup, drink tea and eat crackers. Peter however was not faring too well and he promptly retreated to his bunk after each watch. To give him credit, he never missed a watch, steeling himself for the four hours in the cockpit and returning to his bunk to lie in his meditative state, half asleep and totally in some other universe than the reality that we all now shared.

By day three we were still cruising right along. It was amazing to me that each night the winds and waves would pick up just enough to make the darkest hours feel a little less under control. In the days we were now able to work through the various meals we had packed. Anything was fair game at any time. If you felt like eating, you did. I did most of the cooking and since the wind was steady off the port beam we were constantly healed to the right and I could wedge my self against the sink and deal with the gimbled stove swing through 30 or more degrees as I watched our meals heat up. I was really focused that Peter continue to eat and drink. You never know how people react to these types of conditions. Peter however, had a clear picture of what he needed to do. He ate and drank enough to keep him going and then went to his Zen state where he focused on, I don’t know what, white flowers and such for the eight hours to the next watch.

Going faster was a good thing and though Dan would not acknowledge that there was a possibility of an earlier arrival, we started the math exercises on what we needed to do to cut a full day off the trip. Dan is a conservative passage planner and for good reason. While Vagabond is seaworthy she is normally pretty slow. That however is in the relatively small winds of the Caribbean where she is lucky to do 4.5 knots. Once she began to feel the hard steady 20’s plus she rose to the occasion, cutting through the waves on a 6-knot average. It may not seem like much to most people, picking up 1 mph. We think about such things in an interstate world of 70 mph but if you do the math, and we did, 1 mph over 24 hours is over 24-mile gain in a day! We needed 107 miles per day to complete the trip in 10 days. If we can average 1 mph over what Dan planned the trip at we can cut it to nine. As we rocked and rolled we were all thinking that would be ok with all of us.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing as the wind kicked up very strong again during the night, in the 30’s and we reefed way down and banged our way into the waves. At one point I came up in the middle of the night because the pounding was so loud, and the hull was vibrating so much that I felt that at some point the water might just smash through the hull. The vibrations were so intense that the cabinet above my bunk let go, crashing onto the bunk. I was lucky in that I had put my backpack full of hiking gear under the cabinet which held it up, so it would not smash my head. I knew we had to slow down and we appropriately reefed in the headsail some more. It was still loud, but I could get a little shuteye before my 4 am wake up call. Yes, sleep comes easy when your tired, even though your sleeping bag is wet, the boat is violently crashing up and down, the cabinet is now taking up half the bunk and you need to wake back up in 2 hours for your shift.

It was time to go again, the weather was fair, the outlook good and staying any longer would have resulted in Peter either taking over the ship or him leaving. I’m glad he stayed, he would later wish he had left when he had the chance.

Five hours downwind and leaving the safe confines of the inland reef-protected waters we entered the open ocean and relatively clean sailing. This was short lived as nightfall fell around us. As always happens, if something is going to happen it will happen in the darkness hours. We had chosen, or more accurately assigned our watches. Peter got the mid-night to four am, noon to four pm watch. To me that is the worst, starting and finishing in the darkness. I chose the 4 to 8 am/pm watch. I love watching the sun come up and I psychologically react to the light. Dan took the 8 to noon and 8 to mid-night. As night arrived, so did the wind and waves, going from below 20 to +30 knots and seas reaching more than 10’, and of course it started to rain.

The boat began to rack around, and we heard the crash and breaking of glass. I was just off watch, Dan and Peter were hanging on in the cockpit and I knew the broken glass would end up getting someone cut so, feeling good, I went down and spent the next 30 minutes on my hands and knees picking up the remnants of the French press in the rolling galley. I was a little worried that the conditions would put me over the edge. I am not normally affected by sea sickness, but this was a different story. I was able to get some air, eat a couple of peanut butter crackers then climb down into the bunk for some sleep.

While Peter got the worst watch I ended up with the forward berth. At anchor the forward berth gets the best breeze. In calm conditions it is spacious and comfortable, in rough conditions it moves far more than anywhere else on-board. The bow rises into the wave and crashes down the other side slamming into the back of the wave. On Vagabond it sounded like someone was smashing the front hull with a huge base drum mallet. You could feel the bow shaking. I rolled around in the waves, trying to steady myself and get a flat and comfortable as possible, all the while realizing that my stomach was beginning to feel a little queasy. Usually I can mentally put myself in a frame of mind to see a bout of sea sickness through but as I started burping peanut butter I thought it best to head up to get some air. I didn’t make it and luckily the head was right there as everything came up, for a long time! Who knows if it was just the waves, the cleaning of the broken glass, the peanut butter. All I could think about was Kaylee would feel so vindicated that I had gotten seasick. But I felt so much better now.

I came on watch at 4 am and Peter and Dan promptly crashed. This was Peter’s first hard night of watch and Dan stayed up with him. Eight hours of rain, wind, waves and bashing. As daylight arrived, the seas calmed a little and the rain stopped. We put up more sail, shut down the iron genie and took 25’s off the beam in a much more comfortable 6 to 10’ sea state. Vagabond is a heavy, full keeled boat and does better under sail. Wind off the beam gave her the best possible speed profile. We were able to maintain minimums of 5 knots and often went hours at over 6 and hit 8’s from time to time.

Having the first night to be so rough put us all a little on edge. I was beginning to wonder why I even liked sailing. I was wet (did I tell you that Vagabond leaked from the waves and rain and my bedding was perpetually wet), I was cold (we spent our night-time watches in full foul weather gear with sweat pants and jackets underneath), and it was too rough to really cook anything (if I could have eaten it anyway). The weather did however improve over the day and we all began to fall into our routine, we had nine days to go and getting to New Zealand was the only way we where going to get off this boat.

Because we had done our repairs so fast and the weather window was holding, we were able to call by single sideband radio into the rest of the group that was five days ahead. They had gone through much worse than we had last night, and for much longer. We could only imagine how they fared hanging on in those high winds and waves for three days. The weather had calmed way down for them and they were doing much better. In a few more days all their morale had improved to the point that they seemed to have forgotten the first part of the trip. I'm sure looking at only a couple of days left had a huge impact on their spirits. You could hear it in the radio calls. We still had 8-days.

By the end of the second day I was pretty much back to my normal self, feeling that sailing wasn’t so bad after all. We were able to sip soup, drink tea and eat crackers. Peter however was not faring too well and he promptly retreated to his bunk after each watch. To give him credit, he never missed a watch, steeling himself for the four hours in the cockpit and returning to his bunk to lie in his meditative state, half asleep and totally in some other universe than the reality that we all now shared.

By day three we were still cruising right along. It was amazing to me that each night the winds and waves would pick up just enough to make the darkest hours feel a little less under control. In the days we were now able to work through the various meals we had packed. Anything was fair game at any time. If you felt like eating, you did. I did most of the cooking and since the wind was steady off the port beam we were constantly healed to the right and I could wedge my self against the sink and deal with the gimbled stove swing through 30 or more degrees as I watched our meals heat up. I was really focused that Peter continue to eat and drink. You never know how people react to these types of conditions. Peter however, had a clear picture of what he needed to do. He ate and drank enough to keep him going and then went to his Zen state where he focused on, I don’t know what, white flowers and such for the eight hours to the next watch.

Going faster was a good thing and though Dan would not acknowledge that there was a possibility of an earlier arrival, we started the math exercises on what we needed to do to cut a full day off the trip. Dan is a conservative passage planner and for good reason. While Vagabond is seaworthy she is normally pretty slow. That however is in the relatively small winds of the Caribbean where she is lucky to do 4.5 knots. Once she began to feel the hard steady 20’s plus she rose to the occasion, cutting through the waves on a 6-knot average. It may not seem like much to most people, picking up 1 mph. We think about such things in an interstate world of 70 mph but if you do the math, and we did, 1 mph over 24 hours is over 24-mile gain in a day! We needed 107 miles per day to complete the trip in 10 days. If we can average 1 mph over what Dan planned the trip at we can cut it to nine. As we rocked and rolled we were all thinking that would be ok with all of us.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing as the wind kicked up very strong again during the night, in the 30’s and we reefed way down and banged our way into the waves. At one point I came up in the middle of the night because the pounding was so loud, and the hull was vibrating so much that I felt that at some point the water might just smash through the hull. The vibrations were so intense that the cabinet above my bunk let go, crashing onto the bunk. I was lucky in that I had put my backpack full of hiking gear under the cabinet which held it up, so it would not smash my head. I knew we had to slow down and we appropriately reefed in the headsail some more. It was still loud, but I could get a little shuteye before my 4 am wake up call. Yes, sleep comes easy when your tired, even though your sleeping bag is wet, the boat is violently crashing up and down, the cabinet is now taking up half the bunk and you need to wake back up in 2 hours for your shift.

Daylight comes, you can see the waves, the winds slows and again. Around six or so we are able to let out some of the head sail to keep our speed up. We need to average about 5.6 knots over the next few days to make our nine days voyage a reality.

The last four days of the sail were actually relatively comfortable. I guess everything is relative. Our watches went easily. The most comfortable seat on the entire boat was the watch seat. It was a padded reclining seat and even though it was soaking wet you could get into your foul weather gear and warm sweat clothes, cover your toes with a nice wool blanket that Dan had on the boat and veg out for your shift. We were all actually very happy to service our watches as this was the warmest and least rolly area of the ship. That is of course unless a rogue wave comes around. Peter was on watch and I was sitting on the uphill side. We were cruising along, having some sort of deep conversation such as, do we think the chili is still good after 10 days and can we hold it down (it was, and we did). Peter said something about how the wave heights changed so much and I opened my mouth about how dry a boat Vagabond was, with it’s high gunnels and center cockpit, when suddenly the rogue wave hit me square in the back, just like the sea was listening to us. The wave filled the cockpit and poured into the hatch down into boat. The scuppers drained the boat in short order, there was no damage or danger and after the first couple of seconds of explicative we both had a good laugh. It is best not to be so cavalier about what the sea can do and how it can affect the boat.

The last four days of the sail were actually relatively comfortable. I guess everything is relative. Our watches went easily. The most comfortable seat on the entire boat was the watch seat. It was a padded reclining seat and even though it was soaking wet you could get into your foul weather gear and warm sweat clothes, cover your toes with a nice wool blanket that Dan had on the boat and veg out for your shift. We were all actually very happy to service our watches as this was the warmest and least rolly area of the ship. That is of course unless a rogue wave comes around. Peter was on watch and I was sitting on the uphill side. We were cruising along, having some sort of deep conversation such as, do we think the chili is still good after 10 days and can we hold it down (it was, and we did). Peter said something about how the wave heights changed so much and I opened my mouth about how dry a boat Vagabond was, with it’s high gunnels and center cockpit, when suddenly the rogue wave hit me square in the back, just like the sea was listening to us. The wave filled the cockpit and poured into the hatch down into boat. The scuppers drained the boat in short order, there was no damage or danger and after the first couple of seconds of explicative we both had a good laugh. It is best not to be so cavalier about what the sea can do and how it can affect the boat.

We dutifully listened in on our friends as they cruised into Opua. We were happy they all made it with little damage and were envious that they were done, and we had days left. We listened to xxxxxxx, the weather guru of New Zealand as he gave us our daily weather report. We also had a call into Cheryl each night and she confirmed everything were had been hearing. We were coming into calmer weather, or so he said, and we also found out we had narrowly skirted a bad patch of 40+ knot winds just to our west. We had felt it but only for a short time. A few hours later and we would have really taken it on the chin.

It was only really the last day that the weather completely calmed down. We knew now we would be a day early, our coarse remaining directly toward the Bay Islands. It was foggy as the sun tried to come out early that morning. I was still on watch, Dan was up as he usually is coming onto his morning watch. We figured that we should be seeing the coastline soon, but the fog was obscuring our vision. We had a beer bet on who would see it first when Peter popped his head into the cockpit. Hey what’s happening guys, oh, there are the cliffs, is that New Zealand? He had been in his bunk for days, not moving, then pops up and sees land! Peter buys the first beer!

It was only really the last day that the weather completely calmed down. We knew now we would be a day early, our coarse remaining directly toward the Bay Islands. It was foggy as the sun tried to come out early that morning. I was still on watch, Dan was up as he usually is coming onto his morning watch. We figured that we should be seeing the coastline soon, but the fog was obscuring our vision. We had a beer bet on who would see it first when Peter popped his head into the cockpit. Hey what’s happening guys, oh, there are the cliffs, is that New Zealand? He had been in his bunk for days, not moving, then pops up and sees land! Peter buys the first beer!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed